|

| Washington Evening Star, 25-November-1923 |

This post is part of the Eleventh Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon, hosted by Lea at Silent-ology. A blogathon that has lived for eleven years is a rare and wonderful creature.

- For the first annual blogathon, I wrote about Buster Keaton's time in vaudeville: The 3-4-5 Keatons.

- For the second annual blogathon, I wrote about Buster Keaton and the Passing Show of 1917, the show he signed for after leaving vaudeville.

- For the third annual blogathon, I wrote about Buster's transition from vaudeville to the movies, Buster Keaton: From Stage to Screen.

- For the fourth annual blogathon, I wrote about Buster Keaton's time in the US Army: Buster Keaton Goes to War.

- For the fifth annual blogathon, I wrote about Buster Keaton's time making short comedies with Roscoe Arbuckle, Comique: Roscoe, Buster, Al and Luke.

- For the sixth annual blogathon I wrote about Buster Keaton's First Feature: The Saphead

- For the seventh annual blogathon I wrote about Buster Keaton's Silent Shorts -- Reel One, a series of films produced during 1920-1921. Buster and his team had a very high batting average.

- For the eighth annual blogathon, I started to write about the Buster Keaton shorts produced for the second season, 1921-1923. Buster Keaton's Silent Shorts -- Reel Two

- For the ninth annual blogathon, I wrote about the rest of the Buster Keaton shorts produced for the second season, 1921-1923. Buster Keaton's Silent Shorts -- Reel Two and a Half

- For the tenth annual blogathon, I wrote about the first feature that Buster Keaton had control over, Buster Keaton -- Three Ages -- What the Well-Dressed Man of the Ages Should Wear

For the eleventh annual blogathon, I have written about a feature that was a big step forward for Keaton in the art of storytelling, Our Hospitality.

Be sure to click on most images to see larger versions.

I first became interested in Buster Keaton when I watched The General with my grandfather and he told me how much he had always liked Buster Keaton.

When I discovered that the Anza Branch Library had a shelf of books about movies, I found two books about Buster Keaton, Buster's memoir My Wonderful World of Slapstick and Rudi Blesh's Keaton. I read both and I enjoyed learning about his career in vaudeville and his career in the movies.

Buster made a series of nineteen two-reel comedies in 1920-1922. No one ever asks me, but I tell people that this series of comedies and Charlie Chaplin's series for Mutual are the two best series of silent comedy shorts ever made.

After the short comedies were done, Buster spent the next several years producing a wonderful collection of feature-length comedies.

|

| Film Daily, 07-July-1923 |

While Three Ages was an anthology of three stories set in different eras and places, Buster's next film would "be a costume comedy drama of pre-Civil War days." Buster's wife, Natalie Talmadge, would be his co-star. It was not mentioned here, but Buster would co-direct with John G (Jack) Blystone. Buster's brother-in-law Joe Schenck produced.

|

| Film Daily, 22-September-1923 |

The movie, to be called Hospitality, needed a set representing Broadway and Forty-second Street in Manhattan in 1830. Buster's technical director, Fred Gabouri put it together.

|

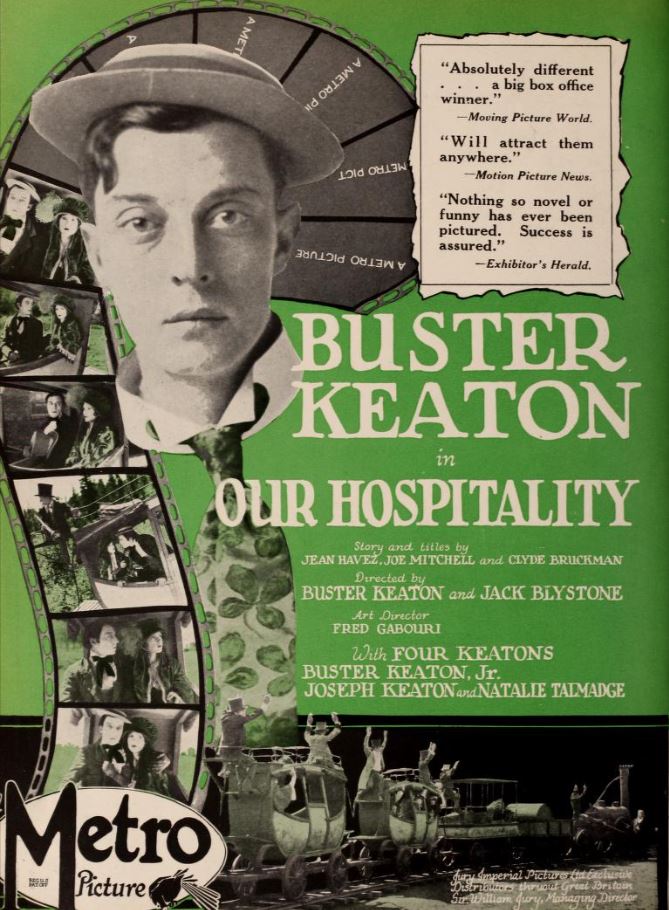

| Motion Picture News, 17-November-1923 |

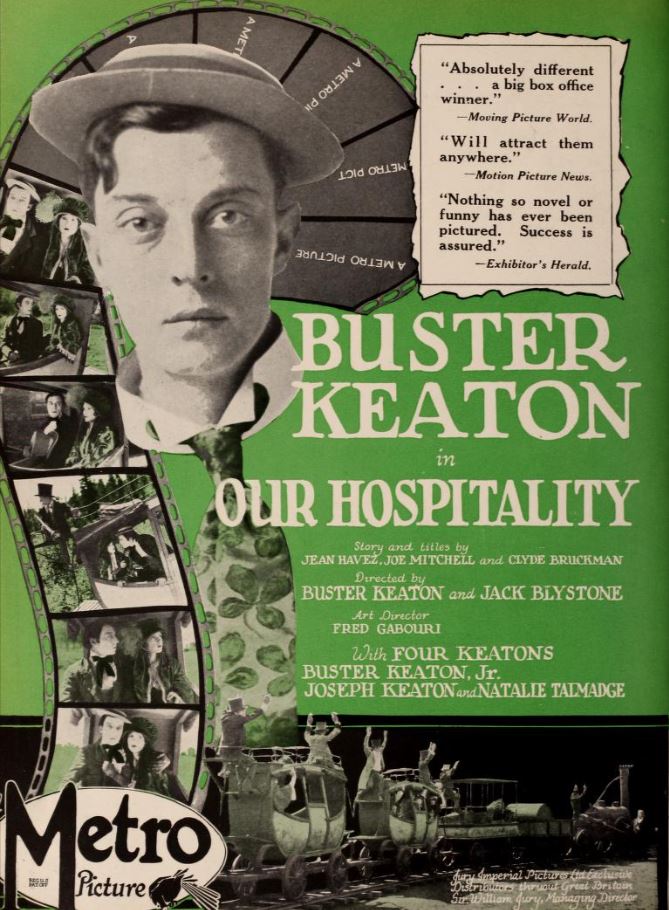

The title of the movie was changed to Our Hospitality. Based on the strong demand for Three Ages, the distributor Metro decided to make "double the usual number of prints."

The film's action is driven by a bloody feud between the Canfield and McKay families. This was inspired by the long and violent Hatfield–McCoy feud. The McCoys lived on the Kentucky side of the Big Sandy River, which is a tributary of the Ohio River. The Hatfields lived on the West Virginia side. Both states remained in the Union during the US Civil War (Kentucky is sometimes called the only state to secede after the Civil War), but both families mostly "took a rebel stand," as the Band said in "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down."

|

| loc.gov |

The Hatfield family poses for a photo in 1897. Family patriarch Devil Anse is the second person in the middle row, with a long scraggly beard and a rifle. Photos of the McCoy family, which was not as well off, are hard to come by.

One man who stayed loyal to the Union was Asa Harmon McCoy. When he returned from the war, a group of Confederate partisans, which included members of the Hatfield family, murdered him in cold blood. This cowardly attack is sometimes regarded as the beginning of the feud.

Things were quiet until 1878, when a McCoy accused a Hatfield of purloining a hog. Justice of the Peace (!) "Preacher Anse" Hatfield, based on the testimony of Bill Staton, who was related to both families, found in favor of the Hatfields. Two McCoys shot and killed Bill Staton but were found innocent because of self-defense.

After dozens of members of each family were killed, the feud slowed down after 1891. Trials of members of both families continued until 1901.

The feud became famous in American folklore. The families came to reconcile during the 20th Century. Members of both families appeared on the gameshow Family Feud -- which seems to be appropriate -- for a week in 1979. The McCoys won the series and received prizes including a pig. Many tourists visit the area where the feud took place.

There have been many movies and television shows, some serious and some funny, some factual and some barely related to the real story, about the feud or inspired by it.

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

|

| listal.com |

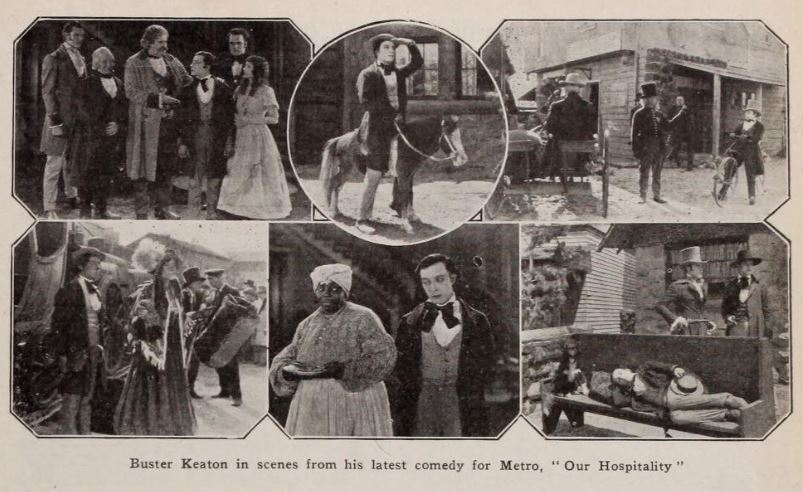

Our Hospitality begins with a serious scene set in 1810. During a stormy night, illuminated by flashes of lightning, the leaders of the Canfield and McKay families shoot and kill each other. This was another step in a long feud. McKay's wife, worried that the feud would consume the life of her infant son, Willie, who is the last of the McKays, flees to Manhattan to live with her sister. Willie is played by Natalie and Buster's son Joseph Keaton, who is billed as Buster Keaton Jr. When the mother dies, the aunt raises Willie and never tells him about the feud.

In 1830, Willie, now played by Buster Keaton, is a not-very-bright young man about town. He takes a ride on a wooden bicycle, called a velocipede. Willie receives a letter from an attorney telling him that he is the heir to his father's estate. Willie imagines a huge mansion. Willie's aunt tells him about the feud, but he insists on going south to claim his inheritance.

Willie catches a train headed south. Speaking as a railfan, I will just mention that this would not have been possible in 1830, since Manhattan is an island and most railroads were not that long. The train is pulled by a locomotive, modeled on George Stephenson's Rocket of 1829. Buster's dad, Joe Keaton, plays the engineer who drives the train. The passenger cars resemble stagecoaches. Willie's faithful dog runs along behind the train, having no trouble keeping up,

At the last moment, another passenger boards the car where Willie is seated. She is Virginia Canfield, played by Buster's wife Natalie Talmadge. They are attracted to each other, but they are shy about it.

The ride is comically bumpy. The ceiling is too low for Willie to put on his tall hat. Willie hits his head repeatedly because of the undulating track, so he ducks under his hat to put it on. A big bump pushes his hat down over his eyes.

Willie replaces his tall hat with Buster's traditional pork pie. This always gets a good laugh in the theater.

I won't go through the rest of the movie in detail, but when Willie gets to the town, he looks for the family estate. He asks a man for directions, who turns out to be one of Virginia's large brothers. He wants to kill Willie but isn't armed. When he borrows a pistol after several attempts, he can't find Willie.

Willie meets Virginia, who invites him to dinner. Virginia's father and brothers hunt for Willie. Willie arrives at the Canfield house. Virginia's father and large brothers realize that they can't murder a guest in their house, so they have to wait till he leaves. Willie figures out that they want to kill him and works hard to stay in the house. When Willie escapes, he passes through some rugged scenery, shot near Lake Tahoe, and winds up in the river. Trying to rescue him, Virginia falls in the river, headed towards a waterfall. Willie rescues her. Willie and Virginia get away from the hunters and get married. Her family has to accept that the feud is over.

|

| Casper Daily Tribune, 01-July-1924 |

"The Greatest Comedy Ever Filmed." Many people must have felt that way. The film was a great success.

|

| Motion Picture News, 19-January-1924 |

Trade ads with color were not cheap.

|

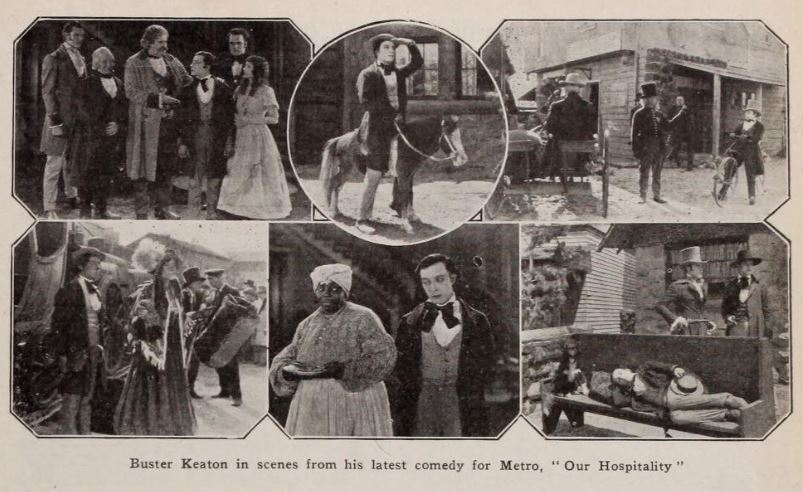

| Motion Picture News, 15-December-1923 |

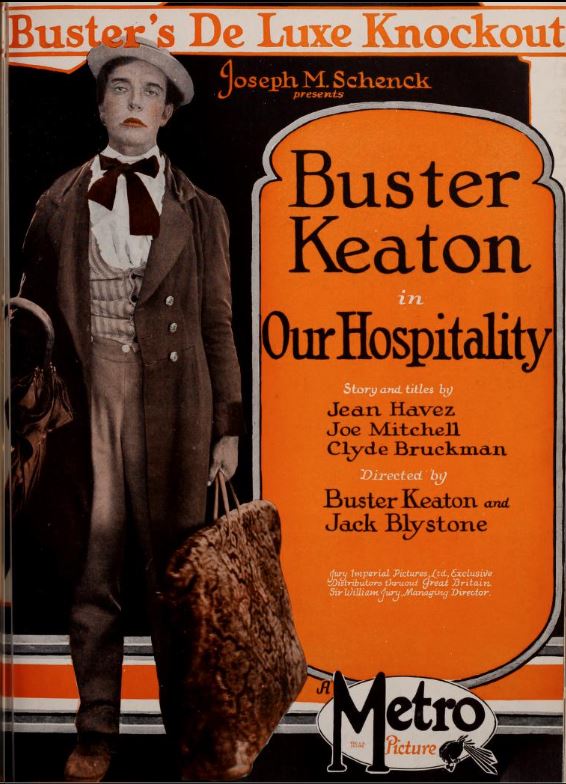

Four page trade ads with color were even more expensive. They did a terrible job coloring Buster's face on the first page.

|

| Motion Picture News, 01-December-1923 |

If you haven't seen Our Hospitality, see it.

|

| themoviedb.org |

I was interested to learn that several Indian movies, including the Bengali language Faande Poriya Boga Kaande Re (2011), directed by Soumik Chattopadhyay, have been adapted from Our Hospitality.

This post is part of the Eleventh Annual Buster Keaton Blogathon, hosted by Lea at Silent-ology. It is amazingly impressive to me to see a blogathon go on for eleven years. Thank you to Lea for all the hard work. Thank you to everyone who visited, and I encourage you to please read and comment on as many posts as you can. Bloggers love comments.